Runcible: Declarative Network Automation

I’m probably better with systems than networks. I’ve got a decent grasp of Networking concepts, but I’ve not worked in large scale environments as a network engineer. I architect-ed the network for a few small (<50 rack) datacenters that were adequate, played with a lot of Linux powered switches, and did a fair bit of edge design with BGP.

On the other hand, as a systems guy I’ve worked in two notable large scale environments at this point, both of which are in the top 500 website list globally according to Alexa (the website statistics service, not the lady-tube). As well as countless smaller, but still pretty large environments. In these environments, some kind of config management for physical infrastructure is absolutely not optional; and can be the difference between being able to scale or being crushed under your own weight. As a result, I’ve developed some strong opinions about configuration management from a user’s perspective.

A while back, I found myself in the position to manage a network again after doing large-scale systems work for a bit, and came to a realization: Open source declarative network automation tools don’t exist.

Now, I know you can use Ansible, Chef, Puppet, and Salt to do a lot of network automation. And I’ve used Ansible and Salt to manage a mixed Juniper/Cumulus environment on several occasions. But trust me when I say the tools aren’t designed to manage networks, they were adapted to it. And if you are a network engineer that hasn’t spent any time on the other side of the fence, you probably don’t know what you are missing out on.

The First Problem: Commonality (A Dependency for Dry Declarations)

The rule of DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) exists for your sanity, and also the longevity of your keyboard. Every programmer lives and dies by DRY. And good configuration management languages should embrace it as well.

But with existing tools, you don’t really get it. At least not for network hardware.

Almost all of the major config automation suites support some kind of hierarchical hash/dict deep merge. For those unfamiliar with the concept, it goes something like this.

layers:

- country

- statecountry:

- name: USA

national_bird: Bald Eagle

national_mammal: Bison

national_flower: Rose

national_tree: Oak Treestate:

- name: Texas

state_flower: BlueBonnet

- name: Utah

state_flower: Sego Lilydeep_merge(country.USA, state.Texas)

national_bird: Bald Eagle

national_mammal: Bison

national_flower: Rose

national_tree: Oak Tree

state_flower: BlueBonnetdeep_merge(country.USA, state.Utah)

national_bird: Bald Eagle

national_mammal: Bison

national_flower: Rose

national_tree: Oak Tree

state_flower: Sego Lily

If you didn’t have deep merge available, you would have to define each entry like this:

item1:

state_name: Texas

national_bird: Bald Eagle

national_mammal: Bison

national_flower: Rose

national_tree: Oak Tree

state_flower: BlueBonnet

country_name: USAitem2:

state_name: Utah

national_bird: Bald Eagle

national_mammal: Bison

national_flower: Rose

national_tree: Oak Tree

state_flower: Sego Lily

country_name: USA

We saved 2 lines of defining by having an inheritance structure, and you can probably tell that the more attributes we define at the country level, the more savings we have.

Merging can save you a lot of pain and boilerplate, especially when you have different servers in different locations with different configurations, but they still share things in common (like what they do, and how the software gets installed.) For servers, the OS serves as an adequate abstraction layer to smooth out hardware differences.

The problem is, no one has the same kind of network hardware at the end of the day, and in a lot of cases you may not even be able to run the same kind of network operating system in two different datacenters, or often, in the same datacenter. If you have an extremely homogeneous environment, you might not notice this problem, but chances are better that you don’t. And even if you do now, you won’t in the future when you inevitably switch platforms.

Using Ansible as an example, lets look at two different configuration snippets:

Juniper:- name: Configure interface in access mode

junos_l2_interface:

name: ge-0/0/1

description: interface-access

mode: access

access_vlan: 2

active: True

state: presentCumulus:- name: Add an access interface on swp1

nclu:

commands:

- add int swp1

- add int swp1 bridge access 2

Both of these configurations do the exact same thing, but as you can see, there is no commonality between them whatsoever. As a result, you can’t have an inheritance structure, which means any changes made to one environment have to be translated by a human and inserted into the other(s). This completely breaks the principle of inheritance.

Moreover, there is no commonality between different types of network hardware (with Juniper being a partial exception to this). Your Cisco Routers and Palo Alto firewalls don’t benefit from the extensive and labeled VLAN dictionary that you use to drive your switch configurations, so you have to repeat information even more.

The Second Problem: Topology is a Thing

Topology isn’t a very important concept in server automation. Things need to be grouped, and you definitely want to keep a few of your application nodes untouched as you upgrade the others. In a lot of cases, you can define a sort of dependency hierarchy, but this doesn’t quite cut it for a network. Networks are all about topology, and trying to pretend like it isn’t important when running automation is a path to ruin.

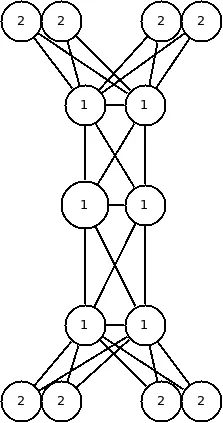

Take the following simple topology:

Group 1 is the role core_switches, and Group 2 is the role rack_switches.

All configuration management suites will give you the option to do a rolling upgrade within a group, which has a high probability of not working in this example. If you are running your operations idempotently, it may not cause a problem, but if you are making a data-center-wide change to your network environment that requires a restart of interfaces; the random choices your automation will make in this case could shoot you in the foot.

If you allow it to run two concurrent applies, and it picks the two middlemost core switches, you’ve just split-brained your datacenter. Or, slightly less worse, it might do a simultaneous apply on both of the switches in a rack, taking the rack down.

The current way to fix this? Just only run against one device within a role at any given time. The problem with this? Some datacenters have a LOT of network devices, as there are only so many hours in the day…

Good network automation tools need to be aware of concepts like adjacency, clustering link aggregation, and pathing. Otherwise you are stuck automating things at a snails pace, or performing dangerous actions.

The Third Problem: Bootstrapping

Lets assume you have a completely homogeneous environment, and you have managed to solve the topology problem mentioned above. If you wind up having to deploy 30 racks, what does your deployment workflow look like? For servers, there is generally a middleman (generally PXE based) that deals with the initial provisioning of a system, and getting it “up enough” into a state where provisioning can be taken over by another system. But many switch ecosystems don’t have this.

What usually happens is that a network engineer will connect a serial cable to a switch, and manually configure it’s management interface to be reachable over SSH or another protocol, then your config management software takes over. More rarely, your ecosystem will support some kind of “phone home” DNS address that can be used to phone home to a server and fetch a configuration file. But for consultants working in smaller environments, this is a non-starter, as that infrastructure doesn’t exist yet (that is what they are in the process of creating.) Also, that infrastructure can’t exist until the network does, so it makes little sense for provisioning network devices.

All of this combines to make the process of bootstrapping switches specifically (but also a horde of other network devices) a royal pain, and often a more annoying task than provisioning a far greater number of servers.

What is Runcible?

Runcible is a Framework and Command Line Application written in python to provide a declarative abstraction layer for configuring network devices. Put simply, it takes a desired state of a set of network appliances (that the user specifies), compares it to the current state of those appliances, and then determines all of the commands that need to be run to correct the differences idempotently. Due to it’s preference for operating on the command-line by default (you can also write plugins that interact with REST APIs), you can utilize the same plugins to configure devices over SSH, Telnet, RS-232, or any text-based CLI.

How Does it Fix Those Problems?

Modular Interfaces

Network devices generally need to comply with networking standards, and Runcible takes advantage of the resultant similarities and provides abstraction layers that can be re-used on multiple different platforms with minimal modification.

As an example, here is a Runcible switch definition for a Cumulus switch in YAML:

meta: # <- Meta module

device:

ssh:

hostname: switch1.oob.domain.net

username: cumulus

default_management_protocol: ssh

driver: cumulus

system: # <- Module

hostname: switch1.inf.domain.net # <- Attribute

interfaces: # <- Module

- name: swp1 # <- Sub-module /attribute

pvid: 22

bpduguard: False

- name: swp2

pvid: 23

bpduguard: True

portfast: True

This example defines three modules, meta, system, and interfaces. Meta is a special module that contains configuration information, and also selects the driver; which is cumulus in this case. The other modules provide an interface to declare the desired state of certain aspects of the switch.

In the system module, we are defining a single attribute; hostname. This controls the hostname of the switch. In the interfaces module, we are defining two sub-modules of the interface type, swp1 and swp2. Inside of these sub-modules, attributes are defined that define the behavior for the individual switchports on the system.

The advantage to these interfaces, is that they are as generic as possible. They try to conform to the standards that each network device follows, not to the language and naming schemes of the individual network device platforms themselves. Each plugin and provider (we will get to those later) can provide their own modules; but they should consume the default ones when possible. This allows the same definition to be applicable to multiple types of network devices of a similar class. In theory, if a switch from “vendor A” supports the same modules as a switch from “vendor B”, their definition files can be completely interchangeable.

Lets look at a practical example of this:

from runcible.api import Device

vlans = {

"vlans": [

{"name": "Employee Vlan", "id": 20},

{"name": "Super Secret Secure Vlan", "id": 4000}

]

}

interface_template = {

"interfaces": [

{"name": "swp1", "pvid": 22, "bpduguard": False},

{"name": "swp2", "pvid": 23, "bpduguard": True}

]

}

switch_1 = {

"meta": {

"device": {

"ssh":{

"hostname": "192.168.1.1",

}

},

"default_management_protocol": "ssh",

"driver": "vendor-a"

},

"system": {

"hostname": "switch1"

}

}

switch_2 = {

"meta": {

"device": {

"ssh":{

"hostname": "192.168.1.2",

}

},

"default_management_protocol": "ssh",

"driver": "vendor-b"

},

"system": {

"hostname": "switch2"

}

}

for configuration in [switch_1, switch_2]:

configuration.update(vlans)

configuration.update(interface_template)

device = Device(configuration["system"]["hostname"], configuration)

device.plan()

device.execute()

As you can see, we have two different devices with two different drivers that support the system, interfaces, and vlans module. Assuming you have a valid plugin for both “vendor-a” and “vendor-b”, you will get effectively the same configuration on both switches (aside from the hostname in this example.)

Intuitively, adding another vlan to the “vlans” list will add it to both of the switches that merge that part of the configuration.

If you aren’t a Python developer, don’t worry. Later versions of Runcible with a more complete CLI component will abstract this behavior into a JSON directory structure. No code required.

Topology Aware Schedulers

One of the priorities of Runcible in regards to topology discovery, is flexibility. Many devices support discovery protocols such as LLDP and CDP, some vendors offer proprietary methods of discovery, many users will want to define the topology manually, and some will be fine with grouping. A lot of people (especially consultants working in a large number of smaller networks) are probably fine with a naive scheduler that runs on one device at a time until they are all done.

As for the decisions that are informed by the topology, that remains to be seen somewhat. Again, the focus will be on flexibility. For many changes, it would be better to have a core -> out run order, for others an edge -> core run order. For less fancy operations, it would probably be fine to determine the run order by choosing devices with the least adjacent runs, or just ensure that only one cluster member at a time is being operated on for highly available devices.

But this will also be one of the final steps in a 1.0 release. The focus for now is a bottom to top implementation of the API functions, meaning that the device API will be more or less complete before the scheduler API is ready, and then a CLI application to wrap all of those will follow.

Operating on the CLI (Or Whatever, Really)

By default, Runcible operates on devices using CLI commands. While this might seem a bit backwards in the {currentyear} REST JSONAPI fervor, it actually has a lot of wonderful side effects. Firstly, any text-based terminal will suffice for configuration. This means that when you go to the datacenter to deploy some switches, you just bring your laptop and clone your definition files locally. Then just plug your serial cable into a switch, and hit go.

Its a simple concept, but very powerful.

So, When Can I Get It?

Right now, this is a project I’m working on in my spare time, so it might be a while. But I’ve been working on solving this problem for a while now, and I don’t have any intention of stopping. I also welcome contributors, so if you want to bring this about faster; be the change you seek in the world!

I Want to Help!

Great! I look forward to working with you!

The best place to get started is here: https://runcible.readthedocs.io/en/latest/contribution_guide.html

Right now you won’t find much, and I haven’t posted any issues on GitHub yet, as the internal class structure is still somewhat in flux. Over the few months I’m hoping to get two somewhat feature complete plugins written for Cumulus and Unifi switches. Once these are complete I will begin a big documentation push in an effort to make the project more friendly to new contributors. Around then, I’ll make an announcement that it is “safe” to make pull requests (when the Plugin structure is stable); but until then any PRs submitted have a high chance of being refactored.

One thing that would be appreciated immediately is installing Runcible, and interacting with the API classes. Let me know how things work out, and how you think the output/public methods should be tweaked for usability and clarity.

I’m also more than happy to take old network equipment off of people’s hands so long as it still runs a relevant network operating system (for things that can’t be run in a VM anyways.) One of the goals that I have in regards to CI is that each build will have all of the core plugins integration tested with their respective platforms, and in some cases hardware is required.